- Home

- Walter E Smith

The Black Mozart Page 5

The Black Mozart Read online

Page 5

Saint-Georges was very busy with his many duties and titles but he found time to continue composing, especially for the stage. In March, 1780, his l'Amant anonyme (The Anonymous Lover) was presented. In the second act, we discover one of those dialogue duets which delighted the music-lover of the day. The complete manuscript score is in the library of the Paris Conservatory. He composed Le Droit du Seigneur (The Right of the Lord). Little is recorded about this work.

Saint-Georges wrote romances which were very popular. They were sung everywhere, as far away as Brittany. A musical company of Rennes put several of them in their program. Their reputation went beyond the English channel to such an extent that "L'autre jour ò l'ombrage (The other day, in the shade of a tree), a romance sung by the delightful actress Louise Fusil during a meeting at the home of the Marquise de Champonas, has been conserved at the British Museum. Louise Fusil became one of St.-Georges' best friends.

Here is one of the stanzas whose words and music were composed by Saint-Georges.

The other day in the shade of a tree

A handsome young shepherd

Sighed into the echo of the wood

His plaintive song:

Such troubles which accompany

The joy of being loved!

You come so reluctantly

and flee so quickly!

Love, let me die:

My mistress has forgotten me:

Life is such a torment

When we are no longer loved.

Saint-Georges, still continuing with his unbelievable schedule, conducted at the Concert of Amateurs, and at the theatre of Mme de Montesson, played violin at the Royal Palace for the Queen, Marie Antoinette, performed his duties as the Lieutenant of the Hunt of Pinci and composed. Another not well known play was written by Saint-Georges entitled Les Amours et la mort du pauvre oiseau (The loves and death of the poor bird). There is no record of exactly when it was written or whether or not it was presented.

Around 1784, he resigned his position as the Superintendent of Music of the Duke of Orléans for unknown reasons and accepted the position of Director of Concerts of the Marquise de Montalembert, maintaining his other position and title of Lieutenant of the Hunt of Pinci. He was in charge at Mme de Montalembert's salon of regulating the musical part and performed certain roles in the plays. The wife of Général Marc René de Montalembert, La Marquise de Montalembert, had one of the best-known salons of that time. Not only the aristocracy was received at her house but good people of other classes as well. To be deemed "homme de beau temp", one had to be received at her house.

Again, as with other hostesses, Saint-Georges was rumored to have been romantically involved with Madame de Montalembert. It was even said that a baby was born from this affair and that the baby died or a white baby was substituted for it. These rumors allegedly came from a former lawyer of the parliament of Paris, Lefebvre de Beauvray, published in the salon of the Parisian Bourgeoisie. This is the same person who is thought to have been the architect of the attack on Saint-Georges and his friend by the policemen in disguise, which I described earlier.

This former lawyer lived not far from the hotel of the Marquise de Montalembert in the faubourg Saint Antoine, rue Popincourt. In the diary he dictated after he became blind, he then had it read by the friends who visited him. He dedicated two passages to Madame de Montesson. Here is what Lefebvre de Beauvray wrote:

One speaks of the gallant intrigues of Mme de La Marquise de Montalembert who still lives with Le Marquis, her husband, rue de la Roquette. According to slander, this young lady was carrying on an affair with the famous virtuoso, M. de Saint-Georges, a rich American Creole. It is even said that a child was born of this illegitimate relationship, but this child died (according to the rumor) sometime after birth. It is said that he could have been cured of the illness which carried him away but he did not receive the necessary care. Perhaps the punitive father, the husband of the lady, took advantage of the circumstances to get rid of a son which he had reason to believe was not his, without fanfare.7

Later Lefebvre de Beauvray wrote:

One no longer sees the sire Saint-Georges on rue de la Roquette. On what strange or foreign theatre has he gone to play the comedy which he no longer plays in public nor in private with Mme la Marquise de Montalembert on the theatre of her strange husband in the hotel occupied here in front of us by Monsieur le comte de Réaumur.

This theatre gives noble presentations but M. le Marquis persists still in refusing to admit commoners and bourgeoisie.

Probably M. Lefebvre de Beauvray was envious of M. Saint-Georges. Whether or not his second-handed rumors or allegations were true, it is obvious that he wanted to do damage with his statements. And why should one doubt that he could have masterminded the assault on Saint-Georges, along with Roland and Pierre?

During Saint-Georges' musical development, he made many new friends in all parts of the theatre. I have already mentioned several who were his teachers, his patrons, and his comrades in the theatre. There was one very famous and exceptional singer, Pierre-Jean Garat, who had great respect for the talents of Saint-Georges. They developed a warm friendship.

Pierre-Jean Garat was a very gifted singer and developed his talent at a very young age. By the time he was in his early twenties, he was already well known and respected as a fine singer. He was the favorite singer of Marie Antoinette, to whom he gave lessons. He gained a great reputation in all the capitals of Europe, and retained his voice for a long period. He became the "first professor of singing" at the Paris Conservatoire and had many famous pupils.

In the biography Garat by Bernard Miall, a portion is dedicated to Saint-Georges. Miall speaks of Saint-Georges in this way:

Another companion of Garat's at this date (around 1787) was the Chevalier Saint-Georges, the idol of half the young bloods of Paris. His father was M. de Boulogne, a wealthy Creole of Guadeloupe, a farmer-general; his mother was a negress. He was, for a mulatto, undeniably handsome; his physique was superb, his muscular strength prodigious; he excelled in every physical sport and as a fencer was supreme. But his attainments were not merely physical; he was, a remarkable violinist, whose skill drew crowds in the garden of the Palais-Royal, when his friends could persuade him to play there by the moonlight. His education had been, for those days, unusually complete; his manners were perfect; he was in short, a coffee-colored Crichton.

A perfect dancer, he rode like a centaur; he was also an unrivaled skater. In the first place master of horse to Mme de Montesson, he was at this time captain of the guard to the Duc de Chartes. It was not strange that this huge, exquisite half-breed had a veritable court of admirers: not only of the opposite sex. The first school of arms in Paris was that of the famous La Boëssière; poet and swordsman, he had taught many of the best swords in Paris, including the redoubtable Saint-Georges. His school, says Thiébault, was the rendezvous of the best fencers...forming the escort, and, so to speak, the court of the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, a true King at-arms, and the first man in the world in all matters of agility, strength, and skill.

You can imagine the effect he produced on me, who yielded to no one in the matter of admiration and enthusiasm...The strongest fencers in the world were all ambitious to fence with him, not to dispute his advantage, but only to be able to say, 'I have fenced,' or 'I fence, with Saint-Georges!'

Saint-Georges had retained a very great deference for his former master, the aged La Boëssière. As soon as he had assumed his lesson: a courtesy lesson, which only lasted a minute or two, but which was very curious to witness...I still seem to see him and hear him call out, in his brusque tone and his great voice: 'That won't do, my children...Begin that again, children!...At the right moment... that's good children, that's good!' And you will understand how this man fascinated us, electrified us.8

A word or two again, regarding Saint-Georges' looks, it was unanimous that he was

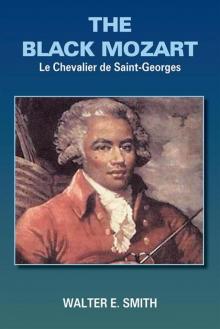

handsome, even his face, although as you may recall, his face was considered ugly by a few. Even with Garat, there is the condescending, "He was, for a mulatto, undeniably handsome." No, Saint-Georges was never completely accepted! In fact, notice that every reference to Saint-Georges mentions him as a mulatto, never a Frenchman or the like. In the following pages are copies of several paintings of St.-Georges, the original one that he sat for and some other artists paintings from memory. You decide.

On August 18, 1787, Saint-Georges presented a two-act piece, prose and ariettes at the Comédie Italienne, which he called La Fille garçon (The Girl Boy). The music of La Fille garçon was received with great applause, if we may credit the Journal de Paris.

Grimm, as I mentioned, gave reviews of two earlier plays by Saint-Georges. Here, he gives a summary of the plot and a critique of Saint-Georges and his music which was not consistent with the views of other critics of the time. He also offers an interesting point of view that should shed more light on the ambivalent feelings of some of Saint-Georges' contemporaries. Grimm wrote:

August 18 (1787) was given on the Théâtre-Italien, the first presentation of La Fille garçon, a comedy in two acts and in prose, mixed with ariettes. The words were by M. Demaillot, who worked with much success for our little theatre of the boulevard and of the Royal Palace. The music is by M. de Saint-Georges, mulatto, more famous by his prodigious talent for fencing, and by the manner, very distinguished, that he plays the violin, and by the music of two comic operas, Ernestine and la Chasse, which did not survive past their first presentations.

The Marquise of Rosane, having had the misfortune of losing her husband and her eldest son in the war, and wishing to save her only remaining son from the same fate, contrived to have her son raised as a girl and gave him to Nicette, the daughter of one of the farmers, for a companion. These two children developed the most tender friendship for each other and this feeling, with age, became love. The indiscretion of a neighbor of Madame de Rosane, who knew the secret, caused the mother and father of Nicette to suspect the truth; these suspicions caused Nicette's parents to hurry the marriage of their daughter with Jean-Louis, the neighboring Miller. Nicette hardly loves him and refuses an engagement that would separate her from her young friend. However, the young Nicette addresses herself to the same Jean-Louis in order to know if he (her friend) is a boy or a girl, as well as to make him suspicious of everything that he felt for some time; the responses of his rival left him uncertain; he (the boy girl) speaks finally to his mother who no longer believes that she can hide the truth. Her son, peaked with joy, then asks her for the hand of Nicette. The marquise tells him how much the public voice would blame a similar misalliance, but the young man attempts to overcome the resistance of his mother who fears seeing him take part in the army. He left her to reappear again soon, redressed in the uniform of dragon that this brother wore, and announces to her at the same time that he is going to go into the service if she persists in refusing him the hand of Nicette. This threat causes Mme de Rosane who consents to the union of the two lovers.

Such is the end of this play that the author, with the aid of several useless scenes, delayed for two acts. Just as the music, although better written than any other composition of M. de Saint-Georges, it appeared equally devoid of invention; the diverse pieces which compose it resemble, and by the themes, and even by the accompaniments, has some too well known pieces. This recalls an observation that nothing has yet refuted, it is that if nature has served the mulattoes in a particular way, by giving them a marvelous aptitude to exercise all the arts of imitation, it seems however to have refused them this zest of feeling and genius that alone produces new ideas and original conceptions. Perhaps also this reproach that I make to nature only involves a small number of men of this race to whom circumstances permitted to apply to the study of arts.9

It was racist then and still is today to suggest that ones color or racial ancestry determines ones ability to be creative. One can see all too clearly that Saint-Georges was sometimes disliked because of his color. M. Grimm's critique could have been one mans opinion had he not tried to be an anthropologist.

I have used many quotes about St.-Georges and his music to help to tell the story of this great man through the eyes of his contemporaries. So many flattering comments were made by so many people that I want you, the reader, to hear about how talented he was and what a wonderful human being he was. It must have been frustrating to be the most talented man around and still have some people who did not accept him. This behavior is the nature of the human being, regardless of race. It exists today and always will. St-Georges endured and prevailed.

In 1788, at the Théâtre des Beaujolais, Saint-Georges presented another comedy with ariettes, titled, Le Marchand de Marrons (The Seller of Chestnuts) and, in 1790, Guillaume tout Coeur.

Thus Saint-Georges' career as a composer ended in 1790. Paris was beginning a great change, indeed all of France was beginning to undergo a revolution that was to last for many years, changing the lives of every Frenchman.

To make clearer Saint-Georges' condition at this time, one must note that the Duke of Orléans died in 1785 and Saint-Georges lost his position as Lieutenant of the Hunt of Pinci. This loss enormously affected Saint-Georges' financial situation, for the position paid well. Remember, Saint-Georges lived well and spent generously.

André Grétry, a famous composer of comic opera, a contemporary and an admirer of the music of Saint-Georges, praised his music in his Mémoires on Music. He commented on one of Saint-Georges' symphonies and said of this particular piece:

This last refrain has been employed in a symphony by the skillful artist Saint-Georges; it is repeated twenty times, and at the end of the piece, one is sorry to no longer hear it.

He went on to relate that:

One night, walking in Thevenat Street, I sat on a street corner to hear this piece that was being played by a full orchestra in a neighboring house: it gave me a pleasure that has not been forgotten.10

This piece was by Saint-Georges.

Saint-Georges left numerous compositions for violin which make it possible for us to appreciate the adaptability and the varied nature of his talent as a composer, while at the same time testifying to his notable gifts as a violinist. He is known to have written: six Quartets for two violins, alto and bass, Op. I (1773); ten Concertos for a principal violin, violins I and II, alto, bass, oboe, flutes and two horns, comprising Op. II, III, IV, V, VII and VIII, which appeared from 1775 on; Symphonies concertantes for two principal violins; further, three Sonatas for the clavicorn or forte piano, with accompaniment of an obligato violin (1781); and finally, a posthumous work, preserved in the British Museum, consisting of Three Sonatas for violin, BIC.I (toward 1801), and of course, his romances and comic operas already mentioned.

Saint-Georges' quartets are written in a clear, flowing ethereal style. More supple, more singing than that of Gossec, his melodies, notably in the rondos, well characterize the sentimental and melancholic mulatto. Saint-Georges was at his best in his Rondeaux, and his little vaudevillian airs had given him a genuine reputation; all are instilled with movement, with grace, and are remembered with ease. We should recall that Haydn, too, chose flexible, lively themes for his finales. It is one of the musical pleasures of the epoch to rediscover symmetric divisions, to repeat incidental melodic phrases. The rounding-out, the return of the phrase in music, declares Grétry; '... makes up nearly its whole charm: In all Saint-Georges' works, the theatrical material shows grace, with a touch of Creole languor. The musician likes to repeat his themes, the second time in the lower octave. Very often, especially in the Rondeaux, they present repetitions of notes which give them a decided spruce ness and elegance.

A dashing and brilliant violin player, Saint-Georges was well aware of the effects to be drawn from motives in larger intervals, which his bow could slash out in bravura fashion. Like most musicians of his day, he showed a stro

ng predilection for the multiple chromatic modulations which give the melodic movement a languorous and velvety touch.

As a technician of the violin Saint-Georges may be numbered among the most brilliant French virtuosi. Not only does he audaciously strive to reach the utmost limits of finger manipulation: he attains them; and in addition his bowing is vigorous and exact. He often plays chord passages at a rapid tempo; he dashingly sweeps up a ladder of skilled treble notes to drop brusquely back upon a deep sonorous tone. Or he carries out his broken-chord effects in the highest positions; in octaves and even in tenths. The suppleness of his bowing permits him to play variegated passages with the most fastidious perfection, and he handles double-stops like a master. He was at once extremely daring and skillful in passages demanding brio and brilliancy, and full of sentiment in the slow movements and Romances to which he was especially devoted. Together with Gaviniès, Le Duc, Bertheaume and Paisible, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges worthy represents the French violin school of the second half of the eighteenth century.11

Saint-Georges was such a great violinist that a story is told that one night, he played a piece of music with his whip, a fact certified by witnesses. The whip in question became legendary; the handle was decorated by an infinity of precious stones and the Chevalier said that every one of those stars of his dazzling collection represented a woman who had loved him.

In 1786, the poet Moline had inscribed below the portrait of Saint-Georges, the following lines:

Offspring of taste and genius, he

Was one of the sacred valley bore,

Of Terpsichore nursling and competitor;

And rival of the god of harmony,

The Black Mozart

The Black Mozart